First, Siberia. There is only one rail line connecting Siberia to the rest of the empire, and positioning a military force there is difficult if not impossible. In fact, risk in Russia’s far east is illusory. The Trans-Siberian Railroad (TSR) runs east-west, with the Baikal Amur Mainline forming a loop. The TSR is Russia’s main lifeline to Siberia and is, to some extent, vulnerable. But an attack against Siberia is difficult — there is not much to attack but the weather, while the terrain and sheer size of the region make holding it not only difficult but of questionable relevance. Besides, an attack beyond it is impossible because of the Urals.

East of Kazakhstan, the Russian frontier is mountainous to hilly, and there are almost no north-south roads running deep into Russia; those that do exist can be easily defended, and even then they dead-end in lightly populated regions. The period without mud or snow lasts less than three months out of the year. After that time, overland resupply of an army is impossible. It is impossible for an Asian power to attack Siberia. That is the prime reason the Japanese chose to attack the United States rather than the Soviet Union in 1941. The only way to attack Russia in this region is by sea, as the Japanese did in 1905. It might then be possible to achieve a lodgment in the maritime provinces (such as Primorsky Krai or Vladivostok). But exploiting the resources of deep Siberia, given the requisite infrastructure costs, is prohibitive to the point of being virtually impossible.

We begin with Siberia in order to dispose of it as a major strategic concern. The defense of the Russian Empire involves a different set of issues.

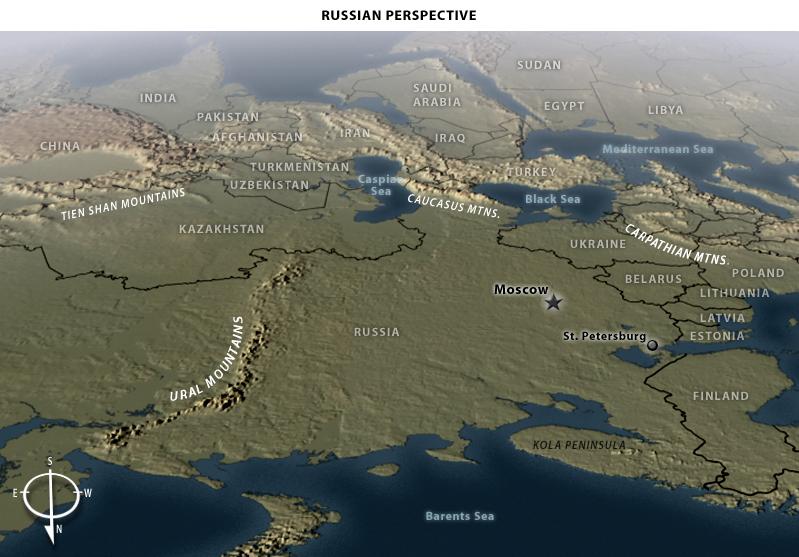

Second, Central Asia. The mature Russian Empire and the Soviet Union were anchored on a series of linked mountain ranges, deserts and bodies of water in this region that gave it a superb defensive position. Beginning on the northwestern Mongolian border and moving southwest on a line through Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, the empire was guarded by a north extension of the Himalayas, the Tien Shan Mountains. Swinging west along the Afghan and Iranian borders to the Caspian Sea, the empire occupied the lowlands along a mountainous border. But the lowlands, except for a small region on the frontier with Afghanistan, were harsh desert, impassable for large military forces. A section along the Afghan border was more permeable, leading to a long-term Russian unease with the threat in Afghanistan — foreign or indigenous. The Caspian Sea protected the border with Iran, and on its western shore the Caucasus Mountains began, which the empire shared with Iran and Turkey but which were hard to pass through in either direction. The Caucasus terminated on the Black Sea, totally protecting the empire’s southern border. These regions were of far greater utility to Russia than Siberia and so may have been worth taking, but for once geography actually helped Russia instead of working against it.

Finally, there is the western frontier that ran from west of Odessa north to the Baltic. This European frontier was the vulnerable point. Geographically, the southern portion of the border varied from time to time, and where the border was drawn was critical. The Carpathians form an arc from Romania through western Ukraine into Slovakia. Russia controlled the center of the arc in Ukraine. However, its frontier did not extend as far as the Carpathians in Romania, where a plain separated Russia from the mountains. This region is called Moldova or Bessarabia, and when the region belongs to Romania, it represents a threat to Russian national security. When it is in Russian hands, it allows the Russians to anchor on the Carpathians. And when it is independent, as it is today in the form of the state of Moldova, then it can serve either as a buffer or a flash point. During the alliance with the Germans in 1939-1941, the Russians seized this region as they did again after World War II. But there is always a danger of an attack out of Romania.

This is not Russia’s greatest danger point. That occurs further north, between the northern edge of the Carpathians and the Baltic Sea. This gap, at its narrowest point, is just under 300 miles, running west of Warsaw from the city of Elblag in northern Poland to Cracow in the south. This is the narrowest point in the North European Plain and roughly the location of the Russian imperial border prior to World War I. Behind this point, the Russians controlled eastern Poland and the three Baltic countries.

The danger to Russia is that the north German plain expands like a triangle east of this point. As the triangle widens, Russian forces get stretched thinner and thinner. So a force attacking from the west through the plain faces an expanding geography that thins out Russian forces. If invaders concentrate their forces, the attackers can break through to Moscow. That is the traditional Russian fear: Lacking natural barriers, the farther east the Russians move the broader the front and the greater the advantage for the attacker. The Russians faced three attackers along this axis following the formation of empire — Napoleon, Wilhelm II and Hitler. Wilhelm was focused on France so he did not drive hard into Russia, but Napoleon and Hitler did, both almost toppling Moscow in the process.

Along the North European Plain, Russia has three strategic options:

1. Use Russia’s geographical depth and climate to suck in an enemy force and then defeat it, as it did with Napoleon and Hitler. After the fact this appears the solution, except it is always a close run and the attackers devastate the countryside. It is interesting to speculate what would have happened in 1942 if Hitler had resumed his drive on the North European Plain toward Moscow, rather than shift to a southern attack toward Stalingrad.

2. Face an attacking force with large, immobile infantry forces at the frontier and bleed them to death, as they tried to do in 1914. On the surface this appears to be an attractive choice because of Russia’s greater manpower reserves than those of its European enemies. In practice, however, it is a dangerous choice because of the volatile social conditions of the empire, where the weakening of the security apparatus could cause the collapse of the regime in a soldiers’ revolt as happened in 1917.

3. Push the Russian/Soviet border as far west as possible to create yet another buffer against attack, as the Soviets did during the Cold War. This is obviously an attractive choice, since it creates strategic depth and increases economic opportunities. But it also diffuses Russian resources by extending security states into Central Europe and massively increasing defense costs, which ultimately broke the Soviet Union in 1992.

In fact as we have seen in p.1 and 2, The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 hit the defense industry particularly hard. Once the premier sector of the Soviet economy, with immense production capacities, the defense industry suddenly found itself without a market. The economic paradigm that supported it was broken and the customers it existed to serve (the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact) were no longer buying.

For a while, the industry was able to sustain itself by feeding off Soviet-era stockpiles of raw materials. But this was hardly a sustainable solution, and as the industry began to consume those stockpiles, it soon had to confront the realities of a completely new economic paradigm: the market economy. The centrally controlled Soviet economic system did nothing to prepare the industry for working in a modern business environment.

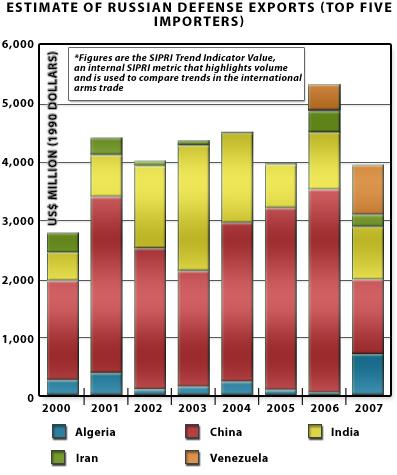

That the Russian defense industry has survived at all is not because of military procurement investment but because of foreign sales. Following the demise of the Soviet Union, China became the principal financier of the Russian defense industry, though Chinese purchases have dropped off significantly. Having learned much from imported Russian military technology, Beijing is becoming quite capable of making its own military equipment. India, Algeria, Venezuela and Iran are picking up the slack as importers of Russian military hardware (and thus financiers of the defense industry).

The bottom line is that the Kremlin, since the end of the Cold War, has yet to invest enough in its own defense industry to sustain it. The new 2011-2020 procurement plan will likely try to do that, but only time will tell whether a reasonable degree of implementation can be achieved.

Meanwhile, Moscow is attempting to eliminate corruption and incompetence and consolidate successful industries under unified aegis like the United Aircraft Building Corporation and the United Shipbuilding Corporation. While much of the defense industry is as bad off as the Russian military during the dark days of the 1990s, certain sectors are nonetheless cranking out quality hardware.

At times, Russian military hardware is still derided by Western analysts who inappropriately hold it to Western standards. This is to misunderstand Russian military hardware. Even the best Soviet equipment was designed with lower quality control, mass production, particularly rugged operating conditions (even by military standards) and crude maintenance in mind.

In fact, the Russian defense industry has made incremental and evolutionary improvements to the best of late-Soviet technology and is able to produce the results and sell them abroad. The Su-30MK-series “Flanker” fighter jets are highly coveted and widely regarded as extremely capable late-fourth generation combat aircraft. The industry is already working on not only a more refined Su-35 but a larger fighter-bomber variant known as the Su-34.

Russian air defense hardware also remains among the most capable in the world. The Soviet post-World War II experience greatly informed the decades-long and still vibrant Russian obsession with ground-based air defenses. The most modern Russian systems — specifically the later versions of the S-300PMU series and what is now being touted as the S-400 (variants of which have been designated by NATO as the SA-20 and SA-21) — are the product of more than 60 years of highly focused research, development and operational employment. Though the S-300 series is largely untested in combat, it remains a matter of broad and grave concern for American and other Western military planners.

That this production capacity has endured through the hardships of the post-Soviet era is simply remarkable, and it represents a solid technological footing for Russian military reform.

While certain Russian products — night and thermal imaging, command, control and communications systems, avionics and unmanned systems — are neither as complex nor as capable as their Western counterparts, they are often more durable and more user-friendly in the hands of poorly trained troops. Products from the T-90 main battle tank to the new Amur diesel-electric patrol submarines are still extremely capable, as are supersonic anti-ship missiles like the SS-N-27 “Sizzler”.

Some of these products come from a Russian design heritage specifically tailored to target American military capabilities (read: U.S. Navy Carrier Strike Groups) and are attractive to a number of customers around the world.

There are two caveats to this. The first is that Russian military hardware is increasingly competing directly with the products of Western defense companies in places like India. Not only is Russian after-market service reputed to be abysmal, but high-profile problems with quality and on-time delivery (though hardly unique) give pause to potential customers with viable alternatives.

The second caveat is that even the newest Russian products have their roots in incremental and evolutionary upgrades from late-Soviet technology, though this is not as problematic as it may seem. Much of the military hardware close to being fielded when the Soviet Union collapsed was quite capable and continues to have very real application and relevance today.

This incremental and evolutionary progression continues, even as Russia’s industry begins to venture into less familiar territory, such as stealth and unmanned systems. These are areas that will require more innovation and present greater challenges and for which there will be less foundation from Soviet days.

This is where the industry’s prospects become particularly cloudy. Declines in both the Russian population in general and intellectual talent in particular have been profound. From software programming to aeronautical engineering, what native talent Russia does possess has been finding work abroad. Those who remain are not attracted to the defense sector, which has done a terrible job of recruiting bright, young employees.

And what expertise the industry does have is nearing retirement age. The youngest engineers with meaningful design experience during the thriving Soviet era (i.e., who were not hired the year before the entire apparatus came crashing down) are already in their 50s, and even those without Soviet experience will be that old within a decade. The financial crisis of the late 1990s prevented the hiring of new workers and the transfer of institutional knowledge.

While Russia recognizes the problems inherent in the defense sector, the window is closing for the transfer of knowledge and experience to a newer generation. Manufacturing can always be outsourced, but without the ability to innovate and move beyond the legacy of late-Soviet designs, the Russian defense industry will be hard-pressed to keep from becoming irrelevant (though it would likely retain some prominence as a small-scale provider of specific — if impressive — niche products like fighter aircraft, air-defense equipment and anti-ship missiles).

To compensate for the erosion in broad capability, the Russian defense sector has occasionally cooperated with foreign countries, notably India and China. Most recently, work on the Brahmos supersonic cruise and anti-ship missile combined Soviet-era research and development with Indian intellectual capital to produce a successful product. Moscow is attempting to replicate this experience with the Sukhoi PAK-FA program to build a modern, stealthy, fifth-generation fighter (though the long-anticipated prototype may prove to be little more than a modified airframe with the engines, avionics and subsystems of the Su-35).

Countries like India and China have essentially used Russia to gain access to late-Soviet design work and to learn all they can in order to create independent domestic defense industries. Some Russian defense equipment is among the best in the world today and, with even moderate upgrades, will remain relevant for a decade or more. But the Russian defense industry has yet to demonstrate the ability to make a bold generational leap in terms of technology. This does not bode well for the industry’s long-term competitiveness and viability.

On Feb. 2 then, during Kyrgyzstan’s president Bakiyev visit to Russia Russian President Dmitri Medvedev made an attempt to counter U.S. influence in Central Asia.

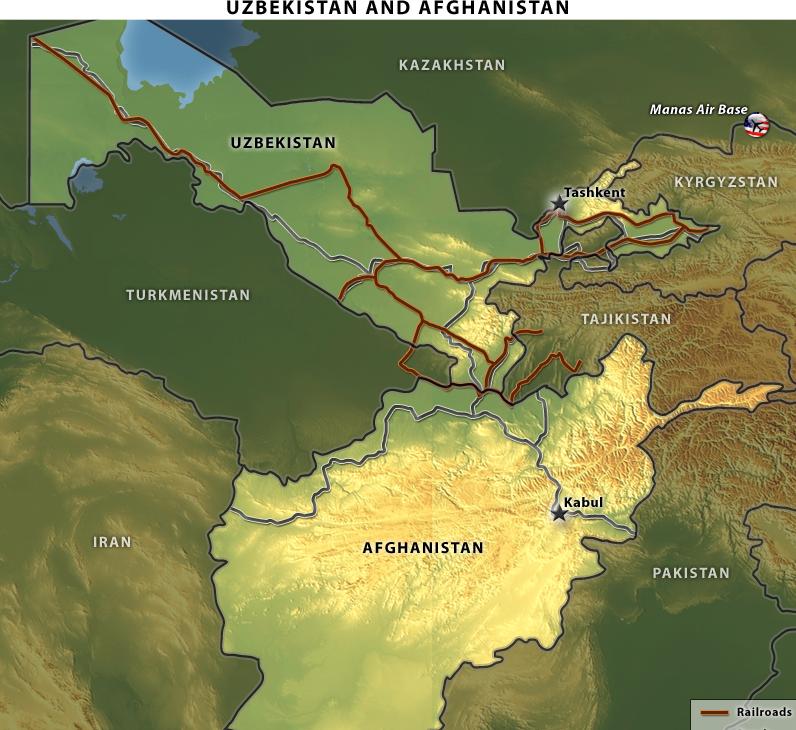

As noted by us before, the new U.S. administration has committed itself to escalating the war in Afghanistan — but its supply lines, which run primarily through Pakistan, are becoming less and less secure. The United States needs a new supply route, and that route must go either through Iran or through Russia’s backyard in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Both routes would effectively require Russian acquiescence. No Central Asian government would be willing to cut a separate deal with Washington without Russian assent, given Moscow’s power and proximity.

Tomorrow we will therefore also discuss a potential alternative route to the Kyrgyzstan one, namely through Uzbekistan.