Updated

version.

After

the comical ‘sofa-gate’ incident in the EU, President Biden is posed

to be the first US President who dares to use the G-word in reference to

the systematic annihilation of Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire between

1915 to 1917. According to estimates, approximately 1.5 million Armenians died

during the genocide, either in massacres and in killings, or from

ill-treatment, abuse, and starvation. The Armenian diaspora marks 24 April as

Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day, a reference Turkey has consistently denied.

Presidents

Barack Obama and Donald Trump, among others, did not use the word to avoid

angering Turkey. Ankara is a longtime U.S. ally and a NATO member. President

Ronald Reagan was the last American leader to refer to genocide in a 1981

proclamation but backtracked under pressure from Turkey. And before Turkey

joined Nato, the “this is not our business”

argument was used.

There

is some indication that many in the Armenian diaspora have not forgotten

Obama’s failure to deliver on his 2008 campaign pledge to recognise

the Armenian genocide and are hoping that Biden won’t follow in the former

president’s footsteps.

Internally,

within the Obama administration, there had been disappointment when he failed

to recognise the genocide, with Samantha Power, who

had served as United Nations ambassador under Obama and and

deputy national security adviser Ben Rhodes both publicly expressing their

unhappiness with the president’s decision.

At

that time, observers had speculated that Obama’s failure to deliver on his

campaign pledge had been rooted in concerns about straining the US’s

relationship with Turkey, whose cooperation it had required on Washington

D.C.’s military and diplomatic interests in the Middle East, specifically in

Afghanistan, Iran and Syria.

Triggering

outrage, foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu threatened that the recognition by

Biden of the mass killings of Armenians will seriously undermine the relationship

between the two countries, including that a scheduled phone call between Biden

and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has now been delayed until further

notice.

Over

many years, because of the fear of alienating Turkey, diplomats have been told to

avoid mentioning the well-documented genocide. In 2005, when John Evans, the

American ambassador to Armenia, said that “the Armenian genocide was the

first genocide of the 20th century,” he was recalled and forced into early

retirement. Stating the truth was seen as an act of insubordination.

For

years, Turkey had successfully deployed an army of high-priced lobbyists to

stop the measure. Ankara spent more than $6 million to press its agenda in Washington

in 2018, according to data compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics, a

campaign finance watchdog group.

The

man who invented the word “genocide”, was Raphael Lemkin, a Polish-Jewish

jurist who was born in 1900 on a small farm near the Polish town of Wolkowysk. Lemkin's memoirs cite early exposure to the

history of Ottoman attacks against Armenians which moved him in 1933 to

investigate the attempt to eliminate an entire people by accounts of the

massacres of Armenians.

Legislatures

in Germany, France and other European countries have however already recognized

the massacre of Armenians between 1915 and 1917 as genocide.

While

Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan had

shared a relatively friendly relationship with former US president Donald

Trump, ties between the US and Turkey have been strained over a range of issues

that include Turkey’s purchase of Russian S-400 defense systems,

foreign policy differences with regard to Syria, human rights and other

intersecting legal issues. Although Turkey had been sanctioned by the US

government under the Trump administration for its purchase of the Russian

defense systems, the former US president had not questioned Erdoğan’s human rights records, which had helped

reduce conflict between the two leaders.

In

retaliation for recognizing the Armenian Genocide, a

New York Times report suggests that Turkey might to try to “stymie or delay

specific policies to aggravate the Biden administration, particularly in Syria,

where Turkey’s tenuous cease-fire with Russia has allowed for already-narrowing

humanitarian access, and in the Black Sea, to which American warships must

first pass through the Bosporus and the Dardanelles on support missions to

Ukraine.”

More

specifically, according to the New York Times report, Turkey could also slow

non-NATO operations at Incirlik Air Base that

American forces use as a base and a station for equipment in the region. The

report indicates that Turkey could engage in provocation that would result in

new sanctions against the country or the re-imposition of the ones that had

been suspended. For instance, Turkey could initiate military action against

Kurdish fighters allied with US forces in northeast Syria.

Also,

more than three months into his presidency, Biden is yet to speak to Erdoğan. Observers say that it is not clear when

relations between the two leaders will improve. Last year during the

campaigning for the 2020 US elections, in an interview with The New York Times,

Biden had called Erdoğan an “autocrat”, which

had drawn criticism from Turkey.

What

happened?

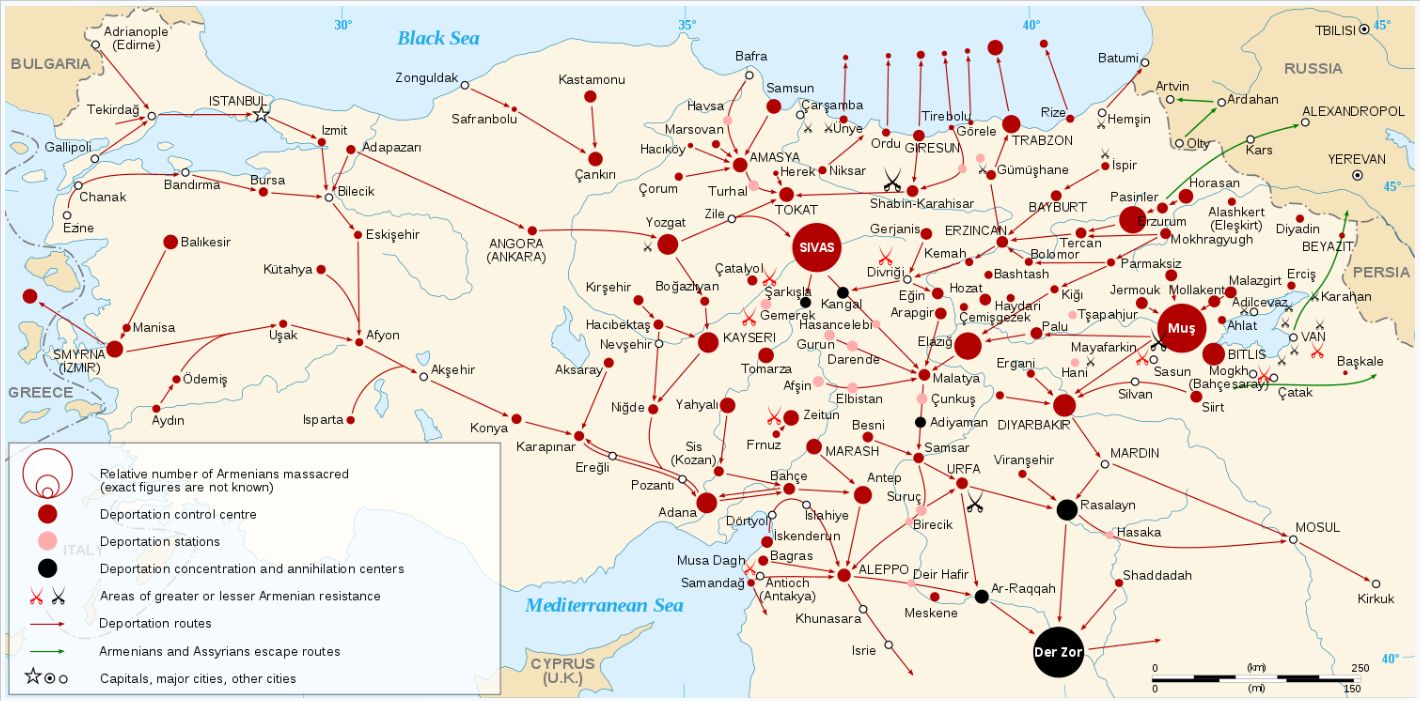

In a

recent (April 2021) book Ümit Kurt writes that; Many

males, including youth, were executed outright, while the rest, men, women,

children, and the elderly, were deported to barren lands in Iraq and Syria.

Those deported were subjected to every manner of misery, kidnapping, rape,

torture, murder, and death from exposure, starvation, and thirst.(1)

Kurt

who among others focuses also on the economic aspects details how Turkish

officials deported the Armenians for various reasons, and while deporting them

promised that the government would look after their properties and give them

their equivalent values in the new places where they would be resettled. All

the promulgated laws and regulations repeated that the Armenians were the true

owners of their properties and that the state undertook their administration

only in the name of the owners. However, the entire legal system was based on

deception and fiction of caring for Armenian wealth and assets. In reality,

these laws and regulations were used to eliminate both the material and

physical existence of the Armenians in Anatolia. The same practice continued in

the Republican era. The Armenians’ right to the properties they left behind was

repeated in the international treaties signed during this period. Turkey

promised to give back properties to owners who as of 6 August 1924 were at

their properties. Afterward, Turkey’s borders were fortified, and not even one

Armenian was able to enter the country.

The

Armenians not allowed back were declared to be fugitive and missing, and the

process of confiscation of their properties continued. Furthermore, as all this

occurred in the Ottoman and Republican periods, it was not and could not be

said that the Armenians had no rights to their properties. Legislation held

that the Armenians possessed rights to their properties, if properties could

not be returned, their equivalent values were supposed to be paid, but that

same legislation was used simultaneously to prevent restitution. The goal was

to completely remove the Armenian presence in Anatolia. What was occurring was

a legal operation of theft. The use of the legal system was both an attempt to

deny and legitimate the Armenian genocide under the cover of legality. The law

was used to provide a legitimation of what was an act of power and destruction.

How

did it happen

In

1908, a new government came to power in Turkey. A group of reformers who called

themselves the “Young Turks” overthrew Sultan Abdul Hamid and established a

more modern constitutional government.

At

first, the Armenians were hopeful that they would have an equal place in this

new state, but they soon learned that what the nationalistic Young Turks wanted

most of all was to “Turkify” the empire. According to this way of thinking,

non-Turks, and especially Christian non-Turks were a grave threat to the new

state.

On

the eve of World War I, there were two million Armenians in the declining

Ottoman Empire. By 1922, there were fewer than 400,000. The others some 1.5

million.

The

evidence in the Ottoman archives is augmented by the documents found in Germany

and Austria, which give ample confirmation that we are looking at a centrally

planned operation of annihilation. See for example Talat Pasha (minister of the

interior): "What we are dealing with here is the annihilation of the

Armenians."(2)

That

time government in the form of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) founded

a special organization that participated in what led to the destruction of the

Ottoman Armenian community. This organization adopted its name in 1913 and

functioned like a Special Forces outfit.

During

the Armenian genocide, there was a great deal of collaboration between the

Special Organization and the Central Committee as well as the local

organizations of the CUP. In the 1919 trial of Unionist leaders, many documents

and several defendants testified to the fact that the Special Organization worked

hand in hand with the CUP, even as it was officially tied to the War Ministry.

The

genocide unfolded in three episodes: first, the massacre of perhaps 200,000

Ottoman Armenians that took place between 1894 and 1896; then the much larger

deportation and slaughter of Armenians that began in 1915 and has been widely

recognized as genocide; and third, as mentioned underneath, the destruction or

deportation of the remaining Christians (mostly Greeks) during and after the

conflict of 1919-22, which Turks call their War of

Independence. The fate of Assyrian

Christians, of whom 250,000 or more may have perished.

The

first episode unfolded in an Ottoman Empire that was at once modernizing and

crumbling, while in chronic rivalry with the Russians. The second took place

when the Turks were at war with three Christian powers (Britain, France, and

Russia) and were concerned about being overrun from west and east. During the

third, Greek expeditionary forces had occupied the port of Izmir, with approval

from their Western allies, and then marched inland.

Under

scrutiny, during the US Senate hearings, there is little doubt that the

death marches that began in April 1915 were centrally coordinated.

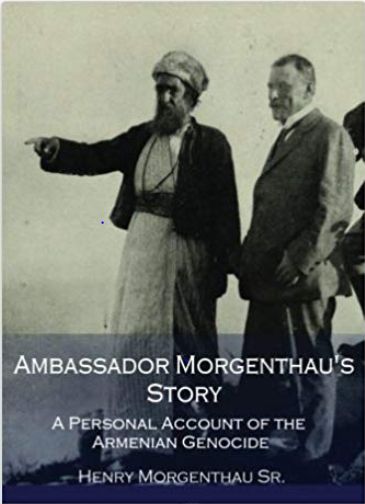

The

facts of the Ottoman campaign have long been established. At the time of the

slaughter, which began in 1915, the American ambassador to the Ottoman Empire,

Henry Morgenthau, cabled Washington that a “campaign of race extermination” was

underway, while the American consul in Aleppo, in what is now Syria, described

a “carefully planned scheme to thoroughly extinguish the Armenian race.”

But

there have been arguments over how long in advance they were planned, and

whether it was always intended that most victims would die.

Ankara

argues that the Armenian death toll was much lower than reported and that

people on both sides died as a result of wartime unrest.

Historians

have contested those assumptions by documenting how Ottoman

soldiers committed massacres and forced

marches that formed part of the Ottoman Empire's mass deportation of Armenians

were instead designed to kill them during the journey.

Based

on current evidence the Ottoman inner circle began planning deadly mass deportations

soon after a Russian victory in January 1915. However, Ottoman policy was also

shaped and hardened by the battle of Van, in which Russians and Armenians

fought successfully, starting in April 1915.

Also

Turkey's allies conceded that the Turkish government had sought to exterminate

the country's Armenian population. For example the Austrian charge d'affaires Karl Graf von und zu Trauttmansdorff Weinsberg, said that the mass of evidence, not only from Armenian

sources but from bankers, German officers, consuls, and other witnesses, led

him to conclude in late September that the Turks, carried out the

"extermination of the Armenian race.(3)

Max Scheubner- Richter, the German vice consul reported to the

German Foreign Office that "there will be no Armenians left in Turkey

after the war."(4)

Recounting

the fate of several thousand missing Armenian soldiers, Leslie Davis, the

American consul at Harput and Mezreh,

wrote that "it finally appeared that all of them were shot by the

gendarmes who accompanied them."(5)

The

American missionary physician Clarence Ussher, a resident of Van for several

years, described a tense city ready to explode amidst rumors of massacres and

reports of murders of disarmed Armenian· soldiers. Even in Ussher's presence, Djevdet Bey gave orders to destroy a nearby community. It

was small wonder, then, that when Bey demanded four thousand Armenian men,

Armenians "felt certain he intended to put the four thousand to

death." On April 19, according to Ussher, Turkish units stationed in

villages around Van received the order that "the Armenians must be

exterminated."(6)

By

the fall of 1915 the physical evidence of slaughter marked the landscape. Roads

and rivers were filled with dead bodies. For weeks corpses, many tied back to

back, floated down the Euphrates River into what is now northern Syria. The

Euphrates briefly cleared, then corpses reappeared, if anything in still larger

numbers. This time the dead were "chiefly women and children."

Travelers on the roads of eastern Turkey also saw the dead everywhere. A

journey outside Harput in November revealed hands and

feet sticking out of the ground, and decomposing bodies: the missionary Mary

Riggs wrote, "The Land was polluted."(7)

But

as mentioned at the start Turkey continues to deny it happened and stopped

anybody searching any of the archives in Turkey. Therefore it might be at its

place here to explain how relevant research nevertheless advanced.

How

the research came about, the revealing bibliography

The

man who invented the word “genocide”, Raphael Lemkin, a lawyer of Polish-Jewish

origin, was moved to investigate the attempt to eliminate an entire people by

accounts of the massacres of Armenians. He did not, however, coin the word

until 1943, applying it to Nazi Germany and the Jews in a book published a year

later, “Axis Rule in Occupied Europe.”

Interest

in the Holocaust, the Armenian Genocide, and genocide as a field of study,

however, more generally began to emerge in the 1960s and subsequent decades.

“Holocaust

consciousness” moved from primarily a Jewish concern into the broader public

with the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961, Hannah Arendt’s controversial

Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), and the growing connection made between the

tragedy in Europe and the survival of the state of Israel. The very term

“holocaust,” which earlier had been applied (by David Lloyd-George, for

example) to the Armenian massacres, now

was nearly exclusively (and with a capital “H”) used for the Nazi killing of

the Jews.(8) With the fiftieth anniversary of the Armenian deportations in

1965, commemorations were held around the world, none more striking than the

demonstrations in Erevan that demanded “mer hogher” (our lands) and led, first, to the removal of the

local Communist party secretary and, later, to the building of an official

monument to the Genocide at Tsiternakaberd.(9)

Armenian “genocide consciousness” fed on

the persistent and ever more aggressive denial by the Turkish government and

sponsored spokesmen, including some with academic credentials, that the Young Turk government had ordered the

deportations and massacres in an attempt to exterminate one of the peoples of

the Ottoman Empire. Actions of Armenian terrorists from 1973 into the early

1980s brought the issue to public attention, but scholarship lagged far behind

the agitated public consciousness. Out of the political and historiographical

struggles of the 1970s came the first serious work by historians in the late

1970s and through the 1980s. Richard G. Hovannisian’s

1978 bibliography of sources on The Armenian Holocaust demonstrated both the

availability of primary sources for anyone who cared to learn about 1915 as

well as the thinness, indeed absence, of academic historical research on the

topic.(10) In those years one had to turn to the French physician Yves Ternon, who moved from his studies of Nazi medical

atrocities to the genocide.(11) As a small number of Armenian scholars, notably

Richard Hovannisian, Vahakn

Dadrian, and Levon Marashlian, as well as a few non-Armenians like Robert Jay Lifton, Leo Kuper, Ternon, and Tessa Hofmann, began to write about an Armenian

genocide, a defense of the Turks by Heath Lowry, Stanford Shaw, and Justin

McCarthy led to clashes over such fundamental questions as the number of

victims, the role and responsibility of the Committee of Union and Progress, and whether 1915 should be

considered an asymmetrical civil war or intentional, state-directed

extermination of a designated people, that is, genocide.

At

the same time, several Holocaust scholars, seeking to preserve the “uniqueness”

of the Jewish exterminations, rejected the suggestion of equivalence between

the Armenian and Jewish genocides. As the historian Peter Novick reports, “Lucy

Dawidowicz (quite falsely) accused the Armenians of

‘turn[ing] the subject into a vulgar contest about

who suffered more.’ She added that while Turks had ‘a rational reason’ for

killing Armenians, the Germans had no rational reason for killing

Jews.”(12)

Armenians

were upset at the reduction of the Armenian presence in Washington’s United

States Holocaust Memorial Museum and by the Israeli government’s attempt to

close down an international genocide conference in Tel Aviv in 1982 after the

Turkish government protested the discussion of the Armenian case.

Prominent

American Jews, including Elie Wiesel, Alan Dershowitz, and Arthur Hertzberg, withdrew from the conference, but

the organizer, Israel W. Charny, went ahead with the meeting.(13) Several

American Armenian scholars, however, refused to attend as well, in protest over

the Israeli invasion of Lebanon that was taking place as the conference held

its sessions. As one state after another officially recognized 1915 as a

genocide, the United States and Israel soon became the two most notable

exceptions, along with Turkey. Activists in Europe and North America organized

a series of campaigns to pressure the holdout states toward genocide

recognition.

Two

years after the crisis over the Tel Aviv conference, the Permanent Peoples’

Tribunal, a civil society organization founded four years earlier (1979) by the

Italian senator Lelio Basso, held a “trial” examining

the Armenian massacres to determine if it constituted genocide. Meeting in

Paris from April 13 to 16, 1984, the jury heard the accounts of scholars, among

them Hovannisian, Jirair Libaridian,

Christopher Walker, Hofmann, Ternon, and Dickran Kouymjian, and examined

the arguments of the Turkish government and its supporters. In its verdict the

Tribunal determined that the “extermination of the Armenian population groups

through deportation and massacre constitutes a crime of genocide…. [T]he Young

Turk government is guilty of this genocide, about the acts perpetrated between

1915 and 1917; the Armenian genocide is

also an ‘international crime’ for which the Turkish state must assume

responsibility, without using the pretext of any discontinuity in the existence of the state to elude that

responsibility.”(14) By the late 1980s, at long last, the first academic severe

scholarship in the West on the fate of the Armenians began to appear in essays,

collected volumes, and comparative studies. A new field of genocide studies

legitimized serious attention to an event that had been all but erased from

historians’ memory.(15) Still, much of the energy spent in these debates

centered on whether genocide had taken place.

Even

as new works appeared, the Turkish official state denial had set the boundaries

of the discussion to the neglect of important issues of interpretation and

explanation. Much of the early literature did not deal explicitly with

questions of causation. A critical intervention by the political scientist

Robert Melson labeled the denialist viewpoint

appropriately the provocation thesis, that is, outside agitators provoked the

Armenians within the Ottoman Empire and upset the relative harmony between

peoples that had existed for many centuries. The Ottoman government’s response

to the Armenian rebellion was measured and justified, in this view, and

therefore it was the Armenians who brought on their destruction.(16)

As a

form of explanation, the provocation thesis remained on the

political-ideological level and made no effort to probe the negative features

of the Ottoman social and political order. No discussion was offered to explain

why the overwhelming majority of Armenians acquiesced to Turkish rule and did

not participate in the rebellion. Nor was any explanation besides greed and

ambition given to explain Armenian resistance. Like other conservative views of

social discontent and revolution, arguments such as those put forth by Western

historians from William L. Langer to Stanford Shaw and Turkish apologists like

the former Foreign Ministry official Salahi R. Sonyel,

repressed peoples had no right to resistance.(17)

Scholarship

on the late Ottoman Empire and the fate of the Armenians burgeoned in the 1990s

and 2000s. Historians of the Ottoman Empire often treated the imperial history

as one primarily of the Muslims, mainly Turks, but in time a broader,

multinational history began to emerge that integrated the stories of the

non-Muslims into the tapestry of the empire.(18) A pioneer in the study of the

Armenian Genocide, the historical sociologist Vahakn

N. Dadrian, made a major, if a controversial,

contribution to the knowledge of 1915 in his synthetic volume, The History of

the Armenian Genocide, arguing that the Genocide resulted from religious

conflict and a Turkish culture of violence.(19) The beautifully written popular

history of poet memoirist Peter Balakian reproduced

in evocative detail the horrors of what happened to the Ottoman Armenians,

though his narrative only hinted at a causal argument and did not attempt a

sustained explanation of why the genocide occurred.(20) Bernard Lewis made the

classical statement explaining the Genocide as the result of conflicting

nationalisms.(21) The argument from nationalism has dominated much of the

subsequent historiography on the Genocide. In an anthology edited by

Hovannisian, Robert Melson, R. Hrair

Dekmejian, Hovannisian, and Leo Kuper explain

the Genocide as largely the result of Turkish nationalist ideology and the

political ambitions of the İttihadist

leaders.(22) An essential (regrettably unpublished) contribution to the local

study of the Genocide was written by

Stephan H. Astourian, the author of

significant articles on the causes, development, and aftermath of 1915.(23) Exceptional work,

indispensable to establish the truth about the often-obscured events of 1915,

was carried out by two giants among researchers and analysts, Raymond Kévorkian and Wolfgang Gust, who collected the relevant

documents that laid the indisputable foundation of facts of genocide.(24)

Perhaps

most extraordinary of all, beginning with the former Turkish activist Taner Akçam, a few scholars of

Turkish and Kurdish origin explored the blank

spots of their history.(25) Even while writing under the restraints

imposed by the denialist state, scholars in Turkey and of Turkish, Kurdish, and

Armenian origins used the available access to the archives and elevated the

writing on the tragedies of the late Ottoman Empire to new levels of

professional authority.(26) The formation

of the Workshop for Armenian-Turkish Scholarship (WATS) brought together

for the first time Turkish, Armenian,

and other historians, sociologists, political scientists, and anthropologists

in a joint discussion of 1915, its causes and

aftermath.(27) Once the static produced by denial was reduced, scholars

were able to focus on the relevant but contested questions of why and when

genocide occurred and who initiated it. Comparison with other genocides yielded

important insights.(28) Among the principal volumes on the Armenian Genocide

that benefited from engagement with an intimate acquaintance with Holocaust

literature are works by the British historian Donald Bloxham.(29) Taking an

international and comparative approach, Bloxham centers responsibility for

genocide on choices made by state leaders, which were shaped by “perpetrator

ideology,” “the most important element in genocide,” and seeks to explain not

only mass killing but also the continued denial of it. Turkish nationalism,

which he sees as “the ideology of the

CUP,” “alone could translate its agenda into mass expropriation and

murder of Christians.”(30) His analysis

employs the notion of “cumulative radicalization,” first used by the German

historian Hans Mommsen to analyze the Holocaust. In a grand comparative study

of ethnic cleansing and modern mass killing, the historical sociologist Michael

Mann suggests a combination of ideological, economic, military, and political

power as essential ingredients in mass violence.(31)

When,

for example, an immanent ideology that reinforces already-formed social

identities combines with a transcendent ideology that seeks to move beyond the

existing social organization, this toxic mix of ideological power increases the

likelihood of violence. Both interstate warfare and the overlapping of

ethnicity with economic inequality increase the possibility of civil and ethnic

conflict. Turning to the Armenian Genocide, Mann rejects the view that Turkish

governments had a consistent, long-term genocidal intent. Like Bloxham, he

emphasizes the radicalization of Turkish policies from the “exemplary

repression” of Abdülhamid II through the

encouragement and then forced application of Turkification, on to deportation

(ethnic cleansing) and finally organized mass killing, genocide.

One

hundred years after the Young Turk government decided to deport and massacre

hundreds of thousands of Armenians and Assyrians the controversies over the

Genocide still rage, but the balance has shifted dramatically and conclusively

toward the view that the Ottoman government conceived, initiated, and

implemented deliberate acts of ethnic cleansing and mass murder targeted at specific

ethnoreligious communities. Although a handful of “scholars” continue to reject

the argument that genocide occurred or to rationalize the actions of the

Ottomans as a necessary, indeed understandable, policy directed at national

security, new generations of researchers continue to establish what happened

and why.

Neo-denialist

accounts occasionally appear, but step by agonizing step more accurate accounts

and plausible explanations are being generated by the present generation of

historians, sociologists, anthropologists, political scientists, and their

emerging graduate students.

A

recent book by Benny Morris and Dror Ze’evi, focused on how from 1894 to 1924, also between 1.5

million and 2.5 million Ottoman Christians perished. As a result, the Christian

share of Anatolia’s population fell from 20 percent to 2 percent.(32)

Sifting

the evidence, Morris and Ze’evi write that the

Ottoman inner circle began planning deadly mass deportations soon after a

Russian victory in January 1915. However, Ottoman policy was also shaped and

hardened by the battle of Van, in which Russians and Armenians fought

successfully, starting in April 1915.

Morris

and Ze’evi conclude that despite the swing from

Sultan Abdulhamid II’s autocracy to republicanism

after 1918, Turkey’s exterminatory patterns persisted, as did the rallying cry

of (domestic) jihad until the early 1920s. Thus, the killing of about two

million Christians purposefully served to Islamize and Turkify Asia Minor,

making it by the early 1920s an almost purely Turkish-Muslim national home and

nation-state.

A day

after US lawmakers passed the resolution Turkey's Foreign Ministry summoned the

US ambassador to Ankara stating that:

"We

condemn and reject this decision of the US Senate," Turkish Vice President

Fuat Oktay tweeted on

today.

There

was also a reaction from a Kurdish commander: This decision will stop Turkey

from committing massacres against the Kurdish people and stop its invasion of

Rojava,” said SDF commander Mazloum Abdi in a tweet,

using the Kurdish name for the Autonomous Administration of North and East

Syria.

Legislatures

in Germany, France, and other European countries have also recognized

the massacre of Armenians between 1915 and 1917 as genocide.

1. Ümit Kurt, The Armenians of Aintab: The Economics of

Genocide in an Ottoman Province, 2021, p.1.

2.

German Foreign Office, Political Archive, PA-AA/Bo. Kons./B.

191, Report of Consul Mordtmann, dated 30 June 1915.

Dr. Mordtmann knew Turkish well.

3.

Armenian Genocide Documentation, vol. 2, 1989, pp. 208, 243.

4.

Political Archive, PA-AA/Bo. KonstB. 170, Report by

Consul Scheubner-Richter, Erzurum, dated 28 July 1915

5.

Leslie A. Davis, The Slaughterhouse Province: An American Diplomat's Report on

the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1917, 1989, p. 61.

6.

Clarence Ussher, An American Physician in Turkey, 1917, pp. 237, 239, 244;

Donald Bloxham, "The Beginning of the Armenian Catastrophe: Comparative

and Contextual Considerations," in Der Völkermord

an den Armeniern und die Shoa,

ed. Hans-Lukas Kieser and Dominik J. Schaller, 2002,

p. 118.

7.

Turkish Atrocities: Statements of American Missionaries on the Destruction of

Christian Communities in Ottoman Turkey, 1915-1917 (Armenian Genocide

Documentation Series) by Ara Sarafian and James L. Barton, 1998, pp. 33,18; and

Wolfgang Gust, Der Völkermord an den Armeniern 1915/16, 2005, p. 353.

8.

Peter Novick, The Holocaust in American Life (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999),

pp. 128–142. “Holocaust” had been used by The New York Times in the 1890s for

the Hamidian massacres of the Armenians, as well as

the Adana massacres of 1910. Duckett Z. Ferriman, The

Young Turks and the Truth About the Holocaust at Adana in Asia Minor, During

April 1909 (London, 1913).

9.

The only historical journal dealing with Armenians available in English in The

1940s and 1950s were The Armenian Review, founded in 1948 by the Dashnak party. Early articles in the journal that dealt

with the Genocide included those by H. Saro (1948), Onnig Mekhtarian (1949), Vahan Minakhorian (1955), Navasard Deyrmenjian (1961), Vahe A. Sarafian (1959), Ruben Der Minassian

(1964), James H. Tashjian (1957, 1962), and H. Kazarian (Haikazun Ghazarian) (1965).

10.

Richard G. Hovannisian, The Armenian Holocaust: A Bibliography Relating to the

Deportations, Massacres, and Dispersion of the Armenian People, 1915–1923 (Cambridge,

MA: National Association for Armenian Studies and Research, 1978).

11.

Yves Ternon, Les Arméniens: Histoire d’un génocide (Paris: Éditions de Seuil,

1977); La cause arménienne (Paris: Éditions de Seuil, 1983); with Gérard

Chalian,The Armenians From Genocide to Resistance, trans. Tony Berrett (London:

Zed, 1983) and Le génocide des Arméniens (Paris: Complexe, 1984); his own

Enquęte sur la négation d’un genocide (Marseilles: Éditions Parathčses, 1989);

and Mardin 1915: anatomie pathologique d’une destruction (Paris: Centre

d’Histoire Arménienne Contemporaine, 2002).

12.

Novick, The Holocaust in American Life, p. 192.

13.

Israel W. Charny and Shamai Davidson (eds.), The Book

of the International Conference on the Holocaust and Genocide: Book One: The

Conference Program and Crisis (Tel Aviv: Institute on the International

Conference on the Holocaust and Genocide, 1983).

14. A

Crime of Silence: The Armenian Genocide, The Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal

(London: Zed, 1985) P. 227.

15.

The work of Leo Kuper (1908–1994) was particularly

important in defining the field of comparative genocide studies: Genocide: Its

Political Use in the 20th Century (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981),

and The Prevention of Genocide (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985).

Among the essential works of the late 1980s and early 1990s were Hovannisian

(ed.), The Armenian Genocide in Perspective (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction,

1986); idem, The Armenian Genocide: History, Politics, Ethics (New York: St.

Martin’s, 1992); and Melson, Revolution, and

Genocide.

16. Melson, “A Theoretical Enquiry into the Armenian Massacres

of 1894–1986.”

17. See,

for example, Shaw and Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey,

vol. II, pp. 315–316; and Langer, The Diplomacy of Imperialism: vol. I, p. 160.

On a particular passage by Langer, Norman Ravitch notes that Langer’s “labeling

of the Armenian movement as national-socialist can hardly be considered a slip

of the pen.” “The Armenian Catastrophe: Of History, Murder & Sin,”

Encounter 57, 6 (December 1981): 76, n. 16.

18.

Excellent examples include Sarkissian, History of the Armenian Question to 1885;

Davison, Reform in the Ottoman Empire; Braude and

Lewis (eds.), Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire; and Hanioglu, The Young Turks in Opposition and Preparation for

a Revolution.

19. Dadrian, The History of the Armenian Genocide; see also his

Warrant for Genocide.

20. Balakian, The Burning Tigris. See the review by Belinda

Cooper, The New York Times Book Review, October 19, 2003.

21.

Lewis, The Emergence of Modern Turkey. Over time Lewis hardened his position.

In 2007 he was quoted in an article opposing U.S. recognition of the Genocide

in the conservative Washington Times: “[T]he point that was being made was that

the massacre of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire was the same as what

happened to Jews in Nazi Germany and that is a downright falsehood. What

happened to the Armenians was the result of a massive Armenian armed rebellion

against the Turks, which began even before war broke out, and continued on a

larger scale.” Bruce Fein (identified as “resident scholar with the Turkish

Coalition of America), “Armenian Crime Amnesia?” The Washington Times, October

16, 2007.

22.

Hovannisian (ed.), The Armenian Genocide in Perspective. For the ongoing

development of Genocide scholarship, see Hovannisian (ed.), The Armenian

Genocide, and Hovannisian (ed.), Remembrance and Denial.

23. Astourian, “Testing World Systems Theory, Cilicia

(1830s–1890s).”

24. Kévorkian, The Armenian Genocide; Gust (ed.), The Armenian

Genocide.

25. Akçam, Armenien und der Völkermord, From Empire to Republic, A Shameful Act, The

Young Turks’ Crime Against Humanity, and with Dadrian,

Judgment at Istanbul.

26.

See, for example, Fuad Dündar, İttihat ve Terakki’nin Müslümları İskan Politikası (1913–1918) (Istanbul: ĺletşim,

2001); his dissertation, “L’Ingénierie ethnique du régime jeune-turc”

(Paris: EHESS, 2006); and idem, Crime of Numbers. Using hundreds of Turkish

memoirs to establish the undeniability of the Genocide, the historical

sociologist Fatma Müge Göçek

produced Denial of Violence.

27.

On the process and results of WATS, see Suny, Göçek, and Naimark (eds.), A Question of Genocide, and Suny, “Truth in Telling.”

28.

Explicit comparisons between the Armenian Genocide and the Holocaust inform two

important collections: Bartov and Mack (eds.), In

God’s Name, and Kieser and Schaller (eds.), Der Völkermord an den Armeniern und

die Shoah.

29.

Donald Bloxham, “The Armenian Genocide of 1915–16: Cumulative Radicalisation and the Development of a Destruction

Policy,” Past and Present, 181 (November 2003): 141–191; idem, The Great Game

of Genocide; and idem, Genocide, the World Wars and the Unweaving of Europe

(London: Valentine Mitchell, 2008).

30.

Bloxham, The Great Game of Genocide, p. 19.

31.

Mann, The Dark Side of Democracy.

32.

The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey's Destruction of Its Christian Minorities,

1894-1924, 2019.

For updates click homepage here