No doubt, given its status

as one of the last frontiers, Myanmar/Burma on many occasions the coming years will be front page news.

Currently under

discussion, the US decision to lift all of its remaining economic sanctions, has surprised many.

As the BBC explains, most

of the US sanctions were targeted - not aimed at the Burmese people but

deliberately focused on key individuals and companies who supported the old

military regime. Thus ending sanctions would effectively take 38 individuals

and 73 companies off the US blacklist. Among them, men who gave the orders to

fire on demonstrators and imprison activists and opposition leaders.There

are businesses that helped procure weapons and others that were dubiously

awarded juicy contracts to build, among many things, Myanmar's

empty capital, Naypyidaw.

While Suu

Kyi seems to have given up

some of her ideals, Myanmar’s ongoing democratic transition has

been a high point of Obama’s time in the White House, a relative success story

in a region where not all has gone according to plan since the administration’s

“pivot

to Asia” in 2012. And recent developments in Myanmar have implications for

U.S. politics beyond Obama’s legacy: Democratic presidential candidate Hillary

Clinton points to progress there as a key diplomatic outcome of her tenure at

the State Department.

The reason for this early

lifting of sanctions can, in my opinion, however also be understood in the

context of the ongoing US attempt to limit Chinese influence over neighboring

Myanmar/Burma as a base for a strategic rivalry between Beijing and Washington.

Whereby already noticed about Hillary Clinton Clinton's 2011 visit to Burma I

mentioned that the lever China could utilize is its ability to direct large

amounts of investment into Myanmar. The United States does not have such a tool

since, unlike Beijing, Washington does not have the authority, ability or

desire to direct U.S. companies to invest in other countries. Such an influx of Chinese funding and investment

could encourage Myanmar to temper its relationship with the United States.

Thus Wednesday’s

announcement marked a significant departure from the incremental easing of

executive sanctions since 2012.

The move to reinstate

Myanmar’s GSP status was made just months after the Obama administration downgraded

Myanmar to the lowest tier status on the annual Trafficking in Persons

report for failing to curb endemic forced labour

tantamount to human slavery. The demotion to tier 3 status opened the

possibility for further sanctions against the country, which Obama in a

contrary move now waived.

Not unlike the BBC various

leading newspapers expressed skepticism, like the

New York Times here, or the Financial Times, calling it “a

major setback” for efforts to weed out corruption in Myanmar, because the US

had given up any leverage it might have had over the process.

In a sign of how opinions

are divided also within Myanmar, itself a proposal by a member of parliament to

lobby for the removal

of US economic sanctions was defeated last month in the Lower House, with

219 votes against and 151 votes in favor. Whereby it is also well known that

the country’s present Constitution gives Myanmar’s military the upper hand by

reserving a quarter of the seats in Parliament for the military, empowering

the military to appoint the ministers of defense, home affairs and border

affairs, and to dissolve the government during a national emergency.

Some experts thus fear the

removal of sanction will hurt the United States’ ability to influence Myanmar’s

most troubled sectors.

Of course the devil is in

the details, the question is how sanctions are removed, and if they will be

removed in a way to leverage some change.

“If the

issue is leverage, the decision today makes almost no sense: Obama and Suu Kyi just took important tools

out of their collective toolkit for dealing with the Burmese military, and

threw them into the garbage,” said John Sifton,

the deputy Washington director of Human Rights Watch.

On top of sanctions

relief, the new trade benefits will allow Myanmar to export of some 5,000

products to the United States duty-free, the U.S. Trade Representative said in

a statement.

Some restrictions remain

in place. Obama’s decision does not normalize relations between the U.S.

military and Myanmar troops. This means no U.S. weapons, equipment, or support

will be sold or given to Myanmar’s military.

However, the White House

on Wednesday advised Congress that America would offer preferential trade

benefits to Myanmar that have been suspended since 1989, one year after the

violent crackdown by the military.

Not surprising the move

has delighted business groups but been sharply criticised

by human rights organizations.

Phil Roberston,

the deputy director of the Asian division of Human Rights Watch,

reacted negatively to Wednesday’s announcement, calling it a dark day for

Burma.

“In one fell swoop, Obama

has let senior military officers, military-connected companies, and crony capitalists off the hook,” said

Robertson.

“Not even Obama contends

the military has undergone reforms, so why is he lifting pressure against a

military that continues to abuse human rights and can remove the civilian

government at any time by declaring a state of emergency?”

For critics of the move,

the lifting of the sanctions means the loss of an important tool that could

have been used to support efforts to resolve rights issue such as the denial of

citizenship to the Rohingya

in Arakan State — a problem that is now being

addressed through a high-profile commission

led by former UN secretary-general Kofi Annan.

“Relaxing of sanctions

should have been benchmarked to improvements like reforming the Citizenship Act

of 1982 and bringing it into line with international standards,” said

Robertson, referring to a law hat has rendered most Rohingya stateless.

“The Obama administration had the option to

keep some sanctions in place, including maintaining the ban on engaging with

military-owned enterprises and keeping targeted restrictions on those

identified as rights abusers,” she said.

Most notably, the

sanctions rollback will derestrict the country’s

dirty jade industry. The jade trade is worth billions of dollars that flow

through tangled channels to shady interests, including illicit gangs and

corrupt military officials. Jade profits fuel ethnic conflict and sustain the

military’s influence, forces that threaten to thwart five years of rapid

progress.

Almost all the jade comes

from Kachin State, but the local population sees

practically no benefits. At the same time, Kachin is

the scene of the country’s most serious armed conflict, which has killed

thousands and displaced over 100,000 more. This is not a coincidence. While

there are certainly other factors driving the violence, research has shown that

jade provides both sides – the Tatmadaw and the Kachin Independence Organisation

(KIO) and Army (KIA) – with incentives and financing to carry on fighting.

For my reporting about the

recent Kachin State situation see here

and here.

As seen, many of the

biggest licensed jade mining companies are controlled by the families of

politically influential retired generals, not least former dictator Than Shwe. Working alongside them are army conglomerates such as

Myanmar

Economic Holdings Limited.

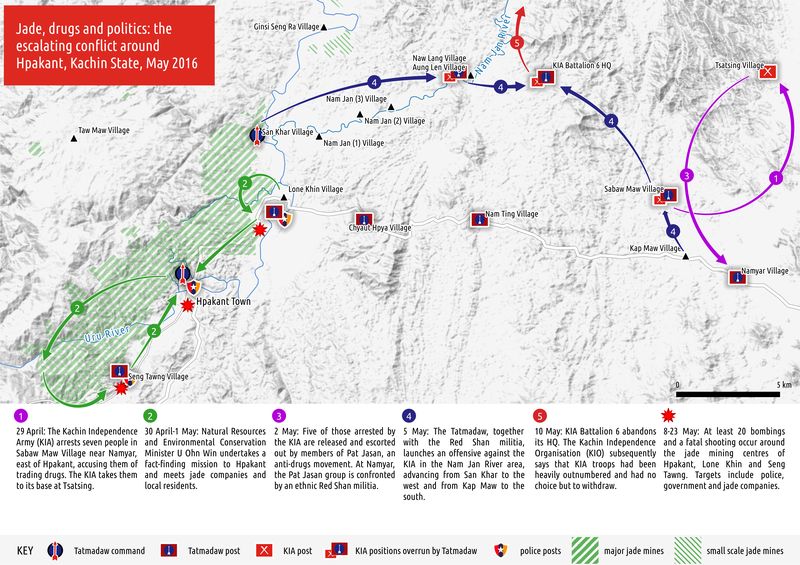

Taking one example, the

May 2016 escalation of fighting around Kachin State’s

Hpakant jade mines clearly showed the threat the

business, in its current form, poses to peace. The army’s offensive came just

days after the current new government asserted itself through a visit

to the mines by Minister of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation U Ohn Win.

Something very similar

happened at the start of 2015 when jade company operations were getting into

high gear following a two-year mining suspension, and as the Thein Sein government was

weighing up an extension of Jade firms’ mining licences.

On that occasion, the KIA detention of a Kachin State

minister and police officers south of Hpakant became

the justification for a major Tatmadaw offensive

against its Battalion 6 base to the north. A series

of bomb blasts followed for which no one claimed responsibility.

As indicated in my 23 Dec.

2015 reporting, similar to what happens with Jade also can be seen in the Burmese-Tatmadaw army

leaders actively participating in the drug trade, whilst at the same

time claiming to be cracking down on it. As a result opium cultivation in

ethnic conflict zones has steadily increased during the recent years and addiction

among ethnic civilians has spiraled out of control.

At the time of writing

also elsewhere in the country government supported clashes force thousands

to flee fighting in Karen state.

At the same time, again

China, not the West or the Obama administration, is the

most important player in the country’s peace process, or talks between the

government, the military and the country’s abundance of ethnic armies. The

West’s participation has been mostly through hordes of private and official

peacemakers who have achieved little more than turning their involvement into a

lucrative industry.

Also the peace

talks that Suu Kyi organised last month were not a success. The United Wa

State Army sent a delegation but they walked

out when they learnt they had been classified as “observers”. It is unclear

if that was their own decision, or did so at China’s

behest.

The success of Aung San Suu Kyi’s

latest trip to Washington may mark a new chapter in Myanmar’s relations with

the United States, but the ongoing civil war in the country gives China control

over crucial levers of pressure on its neighbour that

the distant superpower can hardly match.

What is clear that, while many

more US business will now be able to invest there, the US-China rivalry

over influence in Myanmar/Burma has not ended yet.

There also is no doubt

that the rise of China is an event which threatens America's position in

international affairs. There is growing evidence that the centuries long domination

of global affairs by the West is coming to a close. The key reason is economic

and geopolitics.

Update 19 Sept. 2016: According to The Irrawaddy, the

reaction from China was immediate, with a message in the Chinese media stating

‘‘China

is willing to invest in basic infrastructure projects in Burma that the West is

not willing to invest in," and: Finding a solution to the Myitsone project is important for Daw

Aung San Suu Kyi who needs China’s cooperation in talks with ethnic

minority armed groups operating along the border with China.